Our lab uses a multi-level approach to the analysis of the neural basis of social behavior. We employ a wide variety of social behavior tests (to measure e.g., social play, social recognition, social interaction, social novelty preference, or opposite sex preference), molecular and biochemical assays (measuring hormone, peptide, gene, and receptor expression), stereotaxic surgery combined with molecular and pharmacological manipulations (e.g., altering neuropeptide activation in the brain), and in vivo microdialysis (measuring dynamic release of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters in the brain) to identify the neural mechanisms and circuits important for the regulation of social behavior.

Rodent fMRI analysis (left) and rat brain cryocutting (right)

Dynamic release of neuropeptides during the display of social behavior

There is strong evidence that the neuropeptides vasopressin and oxytocin via activation of specific receptors in the brain play key roles in the regulation of social behavior. However, a major limitation to our understanding of the roles of vasopressin and oxytocin in social behavior is that we know very little about vasopressin and oxytocin synaptic neurotransmission and how this is functionally linked to the display of social behavior. Our lab is among only a few labs in the world that have specialized in measuring vasopressin and oxytocin release within specific brain regions of rats exposed to social behavior tests.

Brain region-specific effects of vasopressin and oxytocin on social behavior

Vasopressin and oxytocin regulate a wide variety of social behaviors, including social recognition, aggression, and affiliation. It is expected that these diverse behaviors each require activation of different brain regions. Vasopressin and oxytocin are synthesized in a number of brain nuclei (e.g. the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, medial amygdala, the paraventricular nucleus, and the supraoptic nucleus) and influence many brain regions (e.g. lateral septum, hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala) due to the wide-spread distribution of their receptors (VP 1a receptor, V1b receptor, and the OT receptor). Using a combination of different techniques, we aim to reveal social behavior-specific brain circuits activated by vasopressin and/or oxytocin.

Neuropeptide regulation of social behavior at immature ages

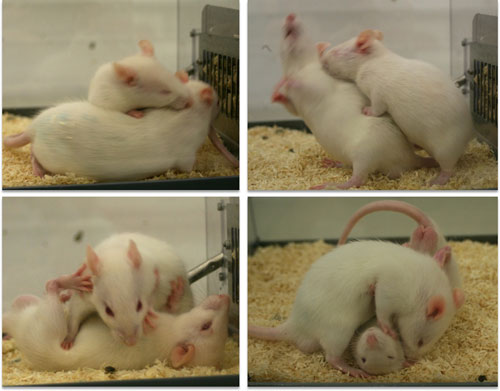

Notwithstanding the current interest in the roles of vasopressin and oxytocin in social behavior, virtually nothing is known about the function of these neuropeptides during development. In this project, we aim to acquire insights in the roles of the vasopressin and oxytocin systems in the development of social behavior. We specifically focus on two important juvenile social behaviors, i.e., play-fighting and social recognition. Play-fighting is common in all mammalian species (including humans) and forms the basis for the development of adequate adult social behavior. In rats, play-fighting is the earliest form of non-mother directed social behavior and peaks at 5 weeks of age. Social recognition consists of the ability to recognize individuals and is essential for all social relationships.

Behavioral function of sex differences in vasopressin and oxytocin

Several psychiatric disorders are sex-biased with a higher prevalence in males (e.g. schizophrenia, conduct disorders, autism spectrum disorders) or in females (e.g. mood and anxiety disorders, borderline personality disorder). This may be due to sex differences in the brain, in behavior, and in sensitivity to stressful stimuli. Understanding the behavioral function of sex differences in the brain is essential towards gaining insights into the mechanisms underlying the sex-bias in psychiatric disorders. The vasopressin and oxytocin systems show robust sex differences in the brain. For example, across different rodent species, males have generally more vasopressin-expressing cells in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial amygdala and denser vasopressin-axonal fibers in the lateral septum than females do (see for review De Vries & Panzica, Neuroscience 2006). However, it is unclear to what extent sex differences in the VP and OT systems cause sex-specific regulation of social behavior.

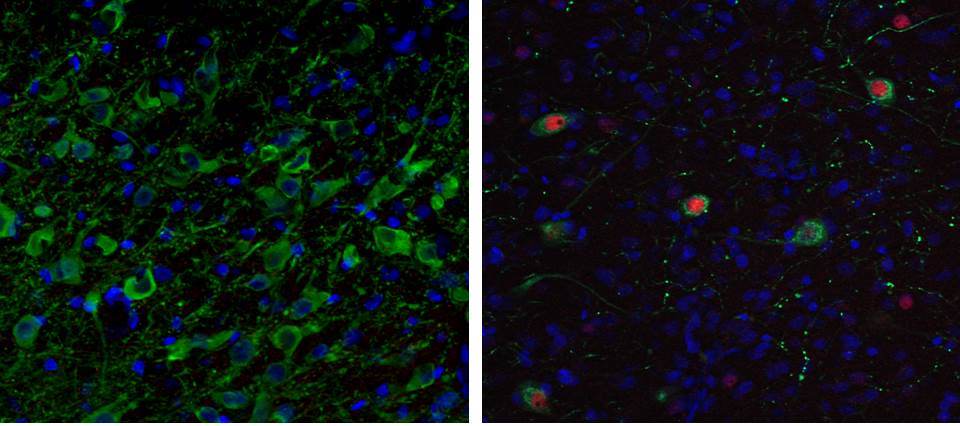

Recruitment of specific neuronal populations/circuits during social behavior

Patterns of brain activation during the expression of a social behavior of interest are assessed by visualizing induction of the immediate early gene c-fos’ protein product (Fos). Fos is a commonly used marker of functional activation (an indirect marker of recent neuronal activity) that can be visualized with immunohistochemical detection techniques. When combined with the use of neuronal tract tracers or visualization of additional neuronal phenotype markers (via immuhistochemistry or RNAScope) this gives us powerful tools to assess the recruitment of specific pathways and neuronal populations during social behavior. The lab also employs chemogenetic approaches (using DREADDS) to learn about the involvement of specific neurons and their connections with other neurons in the regulation of social behavior.

Involvement of neuropeptides in early life stress-induced changes in social behavior

Early life stress (child neglect, child abuse, child trauma, bullying) is a major risk factor for the development of pervasive social deficits that are a key feature of mood, anxiety, and personality disorders. We seek to understand the brain mechanisms underlying social dysfunction in these psychiatric disorders. We employ different early life stress paradigms in rodents to simulate human child maltreatment conditions and investigate the extent to which changes in vasopressin and/or oxytocin contribute to early life stress-induced changes in social behavior.

Maternal separation in rats